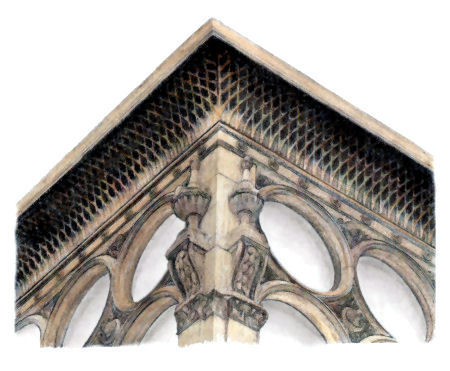

Drawing of cast iron mouldings at corner of Ca' D'Oro Building, Glasgow

Glasgow was a European pioneer in the use of cast iron and steel for commercial

buildings. The use of these modern materials, which led the way to the early skyscrapers

in North America, was developed by local architects and foundries to provide cost-

efficient floorspace in Victorian Glasgow's thriving business district.

The rapid urbanisation of Glasgow in the early 1800's had created an

unprecedented building boom which led to the fabrication of cast iron buildings. Looking at some of the semi-derelict buildings in this area you can gain an insight into how the building styles and construction methods evolved. The example (right) features prefabricated ironwork in both internal and external construction elements. The tell-tale signs of rust on the slim cast iron window frames give a clue that new factory-produced materials were involved in the construction process.

By the time of the Carswell brothers' deaths in the mid-1800's, the industrial areas of the expanding city contained 122 furnaces, burning coal from 37 local pits to produce over a million tons of pig iron annually. An indication of the huge demand was demonstrated on 14th December 1855 when the Glasgow Herald reported that weekly cargoes of Irish ironstone were arriving from Ballycastle, County Antrim, to supplement the flagging supplies of Scottish ore.

The rich deposits of indigenous black-band ironstone which had been discovered in Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire in the early 1800's were completely exhausted by the end of the century.

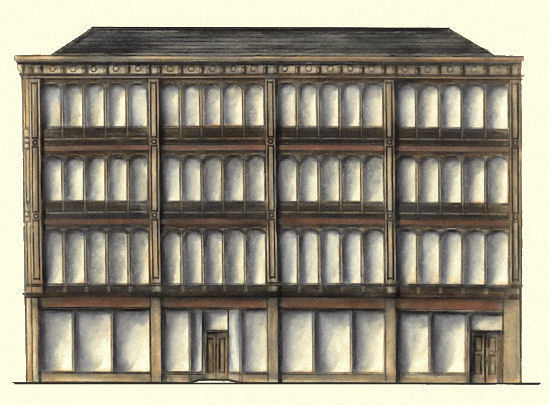

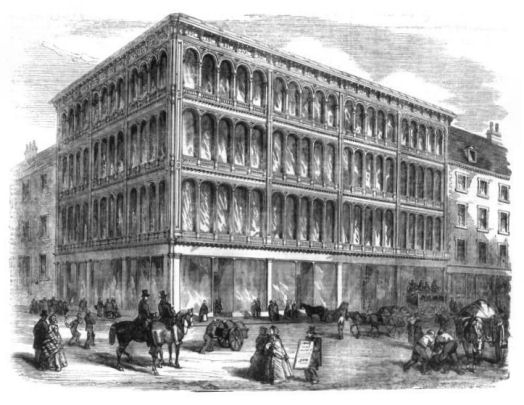

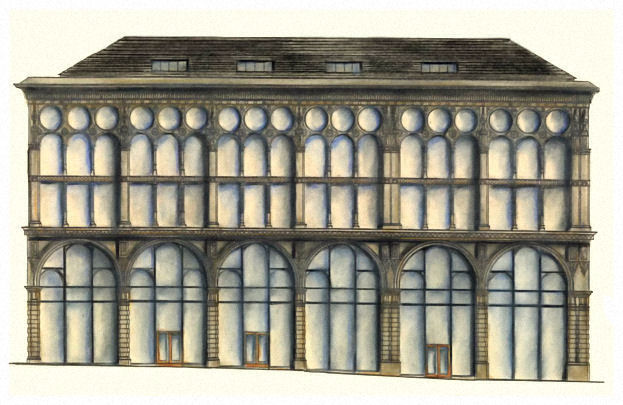

Gardner's Warehouse

Gardner's Warehouse in Jamaica Street, south of Argyle Street, dates from 1856 and is the oldest completely cast iron fronted commercial building surviving in Britain.

The engraving below, from around the time when the warehouse was built, shows a rather incongruous scene, where the modernity of the building is contrasted with the happenings in the street. The view below shows the same scene in the summer of 2005, nearly 150 years later, when nothing of much interest was happening in the street. The building has survived the ravages of time much better than we would now expect using modern construction methods

Gardner's Warehouse had been supplied with all the latest fixtures and fittings including one of the earliest ever safety elevators, imported all the way from New York City. This type of elevator had been invented by Elisha G. Otis in 1852. Original Otis elevator at Gardner's Warehouse, imported from the USA in the 1850's

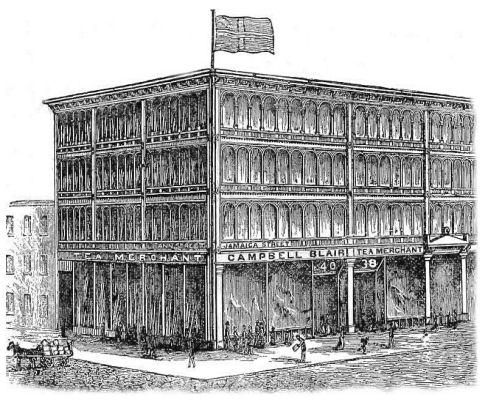

Ground floor shop unit at Gardner's Warehouse let to Campbell Blair, Tea Merchants, 1866

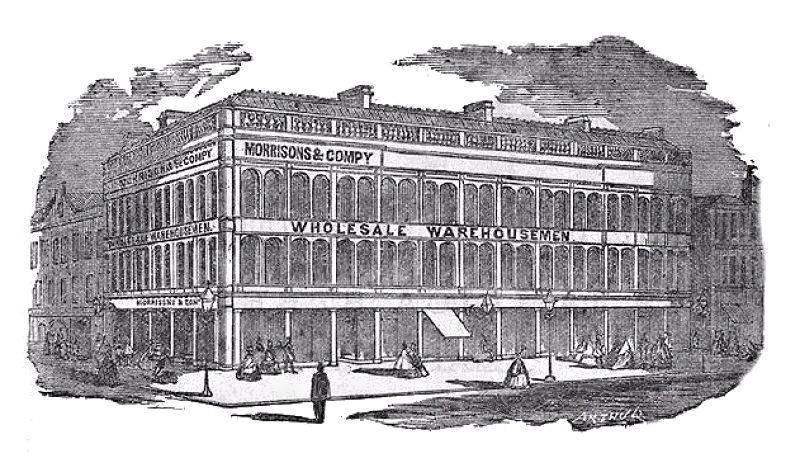

Around the same time, a very similar warehouse was built across the road on the eastern side of Jamaica Street at the corner with Howard Street. Hugh Morrison & Co.'s warehouse of 1857 had almost identical cast iron elements to Gardner's Warehouse. Morrison's store was later occupied by R.W. Forsyth, the famous Glasgow outfitter. The building was demolished around 1924/1925 and replaced with a Royal Bank of Scotland branch, probably because of its valuable corner site on the approaches to St Enoch Square.

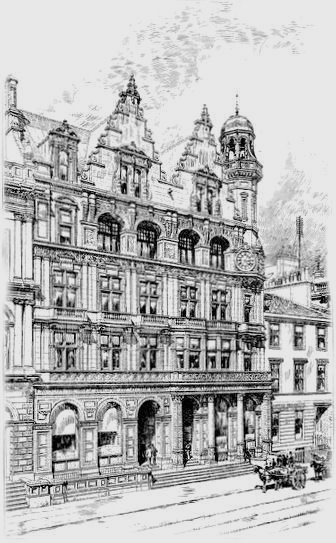

Engraving of Morrison's Warehouse on east side of Jamaica Street, at corner with Howard Street

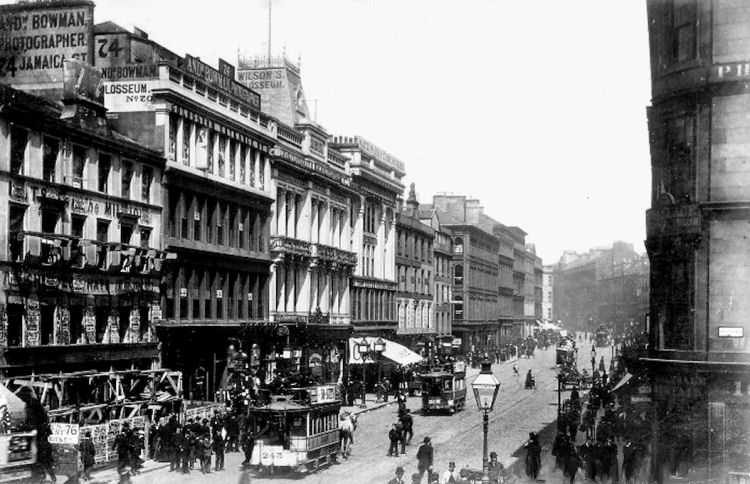

South of Gardner's Warehouse, heading towards the riverside, a fine range of iron framed buildings with continuous balustrades could be found at 60-74 Jamaica Street. While in the occupation of Walter Wilson & Co. all three blocks were collectively known as the "Grand Colosseum Warehouse", sharing the title of the central store which had some exterior masonry surrounding its iron frame. It was flanked on either side by two buidings with façades fashioned entirely from cast-iron.

Range of iron framed buildings in Jamaica Street, centred on Grand Colosseum Warehouse

View of warehouses in Jamaica Street from the north-east

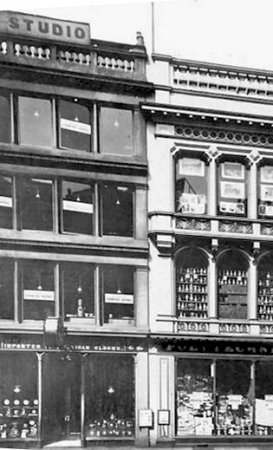

The block at 72-74 Jamaica Street at the southern end of the Grand Colosseum group was designed by William Spence and constructed about 1854. The modernistic façade had numerous panes of plate glass contained within slender iron columns. There were masonry walls at either end abutting adjacent blocks.

Plate glass fronted warehouse at 72-74 Jamaica Street

The Photographic studio of Andrew Bowman was situated on an upper floor of the building, The studio specialised in typical Victorian portaiture with the subjects in standard stylised poses.

Andrew Bowman's Photographic Studio at 74 Jamaica Street

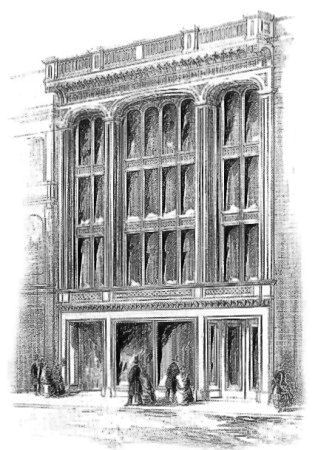

The northern section at 60-66 Jamaica Street contained the offices of Walter Wilson & Co. proprietors of the Grand Colosseum Warehouse. The innovative triple arched cast-iron façade of the structure, which dates from 1857, was designed by the partnership of Hugh Barclay and Alexander Watt.

Engraving & photograph of cast iron fronted warehouse at 60-66 Jamaica Street

Entrance to central portion of Colosseum Warehouse, Jamaica Street, c.1900

The central portion of the Colosseum Warehouse was designed by Hugh Barclay in 1857. The internal view below shows the arched iron framework behind the exterior frontage. The retail space had rows of parallel iron columns allowing lots of open areas to display the goods and allow the customers to circulate.

In the department displaying ladies' gowns the iron columns were hidden behind mirrors. Perhaps their sight could have disturbed the sensitivities of the clientelle?

Mirrored columns at Colosseum Warehouse, Jamaica Street

Jamaica Street warehouses prior to demolition

This view of Jamaica Street is from some time before the electrification of the Glasgow tramways in 1902. It features timber scaffolding around a shop which is in the process of having a replacement display frontage installed.

Horse-drawn trams in turn-of-the-century view of Jamaica Street

Ca' D'Oro Building, Union Street / Gordon Street

The Ca' D'Oro building, situated close to Glasgow Central

Station, was completely rebuilt behind its retained façade in 1989, over a

century after it was built. The Union Street frontage was enhanced with two

additional bays, finished with cast iron mouldings which are exact reproductions

of the originals. In the 1920's, the luxurious Ca' D'Oro Restaurant, which took

its name from the gilded 15th century Ca' D'Oro Palace in Venice, occupied all

the upper storeys. At street level the shops have sculpted stone pilasters

surrounding the cast iron frame, which becomes much more decorative on the

upper tiers. The photograph (left) was taken on a clear mid-winter's day when

the reflective qualities of the glass allowed the windows to be viewed

to their best effect. Thankfully the old building's incongruous 1920's metal

window frames have been replaced with large panes of fixed glass. The natural

light is further augmented by a glazed atrium roof illuminating the central core

of the building.

The ironwork at the upper levels is worthy of close inspection

for the intricate detailing which was designed and cast at the Saracen Iron

Foundry in Glasgow. The window frames are in the form of open ended figures of

eight, a familiar feature of the Venetian style.

Walter Macfarlane's Saracen Works were the Scottish counterpart of Daniel Badger's Architectural Ironworks in New York City. Both foundries mass-produced highly ornamental architectural elements which the architects of the time could readily select from manufacturers' catalogues to fit into their designs. The drawing, right, shows a scene from one of the palatial showrooms attached to the foundry. The showrooms covered an area of three quarters of an acre, displaying all manner of architectural ironwork.

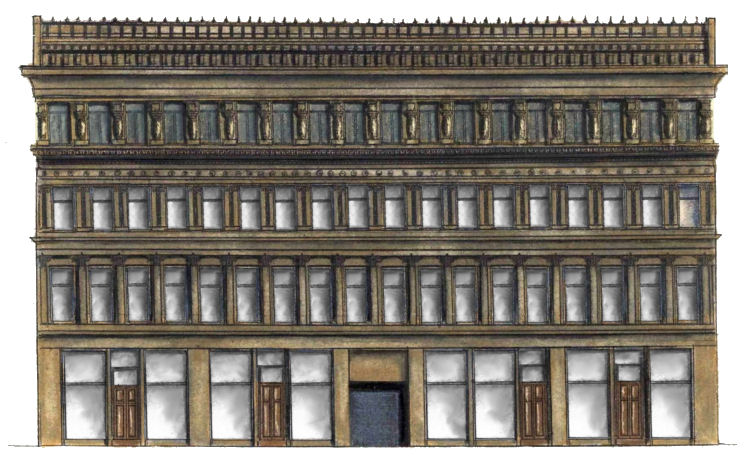

Glasgow's most famous Victorian architect, Alexander Thomson, did not restrict himself to designing unique churches and

houses. His warehouses and office blocks are not the ordinary run-of-the-mill buildings of the

day but are further examples of his design genius. Thomson's innovative approach to design reached a new level in 1873 when his most famous commercial work, Egyptian Halls (below), was built.

Egyptian Halls, 1873

Alexander Thomson's Egyptian Halls, on the eastern side of Union Street, is

a well-disguised commercial building behind an elaborate façade. The magnificent frontage has a row of

shops at ground level. Above the shops the exterior is different at every storey, displaying a highly original selection of exotic themes. Upper levels of Egyptian Halls, Glasgow

This interior view of Egyptian Halls shows cast-iron columns supporting the continuous floors which were formed with a loose clinker concrete reinforced with iron joists.

There was a £3 million proposal in 1996 to demolish and redevelop the block behind a retained façade in a similar way to the nearby Ca' D'Oro building. This scheme was abandoned when the joint owners failed to reach agreement.

In September 2012 I was invited to look round the and take photographs inside the Egyptian Halls,

by Derek Souter of Union Street Properties Ltd.

The drawing, right, details the first floor windows over the shop fascias in Union Street. It is somewhat idealistic, giving an idea of what it should/ could look like if the money was found to clean and restore the blackened stonework to its original condition.

The decoration at this level of the façade features many of the familiar motifs and emblems which can be seen inside and outside Thomson's houses, churches and commercial premises throughout the city.

The most ostentatious use of cast-iron in the city can be seen in Thomson's St Vincent Street church where the gallery is supported with rows of slender columns with disproportionately large capitals, featuring maritime and botanical motifs.

I have created a page featuring many of the offices and warehouses of Alexander Greek Thomson. It also features illustrations of his houses and churches built in Glasgow.

Cast iron warehouse abutting huge cast iron bridge at Glasgow Central Station

Cast iron façade of Scottish Music Centre, Merchant City

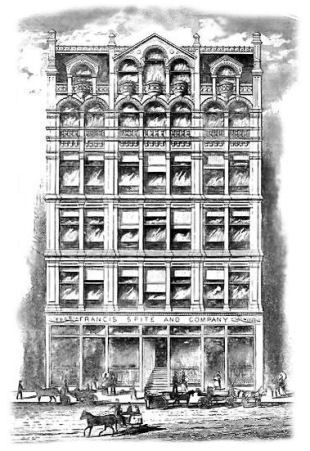

The fine cast iron and glass façade of Spite's Warehouse in St Enoch Square was spoiled in 1932 when the columns were replaced by plain stone mullions. The style of building simply wasn't appreciated at the time! Original cast iron façade of Spite's Warehouse, St Enoch Square

Cast iron and glass framed railway shed at Queen Street Station, Glasgow

The best surviving example of the interior use of decorative cast iron in Glasgow can be found at the former Fish Market in the Briggait. The Victorian market hall closed in the 1970's and was threatened with demolition as no long term alternative use could be found for it. In 2010, after a decade long period of refurbishment, the building was successfully transformed to create 45 artists' studios and 24 office spaces surrounding the central courtyard, which had previously functioned as the market hall. Interior view of trading hall at former Fish Market, with studios built around the iron frame

Internal detailing of ironwork at former Glasgow Fish Market

The oldest surviving iron-framed fireproof industrial building in Glasgow is a former cotton mill in Old Rutherglen Road, Gorbals, which was latterly known as the 'Twomax' clothing factory.

The various levels of the building had brick arched ceilings supported by double rows of cast-iron columns at each floor. The top storey with its large glazed studio windows was a twentieth century addition to the original block. An engraving showing the factory in its original state can be seen at the Hutchesontown, Gorbals page of this website.

Derelict Warehouse, Gorbals

This derelict warehouse at Coburg Street, Gorbals, shows the outline of an adjacent demolished building in the brickwork.

Many of the most modern office blocks in Glasgow city centre are hidden behind the shells of 19th century buildings. Façade retention, Ingram Street

By the 1880's the mid-century fashion of iron framed buildings with cast-iron moulded frontages had long since passed and any clues to construction methods were carefully hidden behind decorative sandstone exteriors. Stone faced office block at West George Street, J.Macleod Architect, 1881

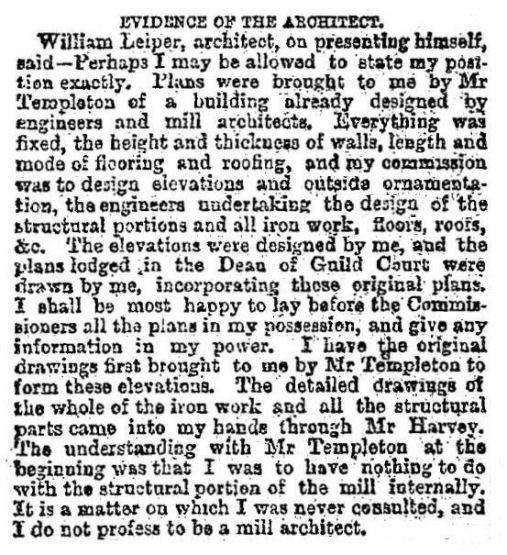

Glasgow’s most spectacular industrial building has to be Templeton’s Carpet Factory at Glasgow Green which was completed in 1892. William Leiper's extravagantly decorated Venetian Gothic frontage was faced with multi-coloured bricks and finished with sandstone dressings. Templeton's Carpet Factory, Glasgow Green

In the 1980’s the building was extensively restored and converted into the Templeton Business Centre. Its current use is as a residential block.

On 1st November 1889, during the building's construction, there was a partial collapse of the external facing wall, with masonry crashing through the roof of an adjoining weaving shed resulting in the deaths of 29 female workers and many serious injuries.

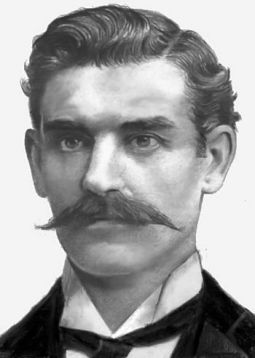

The extract below from the Glasgow Herald of 21st December 1889 is from a report of the public inquiry following the accident. It gives Leiper's account of his involvement in the design and construction of the factory prior to the tragedy. He claimed to be responsible only for the design of the elaborate façade. The factory and its structural ironwork was designed by Messrs J.B. Harvey, mill engineers.

The inquiry highlighted discrepancies in the evidence of William Leiper (left) and Alexander Harvey regarding their respective responsibilities. The two men appear to have been only interested in saving their own reputations with no acknowledgement of any individual or collective liability and no apologies to the families of the victims of their presumed negligence. The published report concluded that the exterior wall would probably have been unstable during the period of construction whereas the structural integrity of the completed building would have been satisfactory. It appears that the façade was not properly tied into the framework of the mill during the construction process. Regrettably the inquiry's remit did not involve the apportionment of blame for the incident.

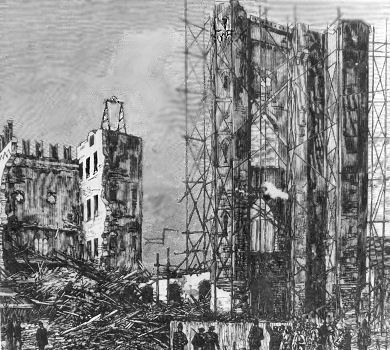

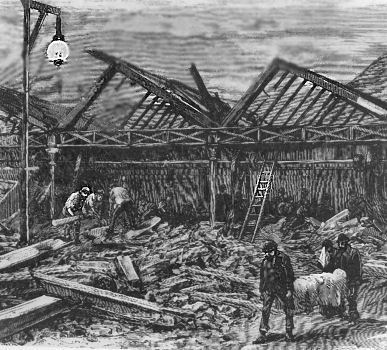

Contemporary images of aftermath of accident at Templeton's Carpet Factory, 1889

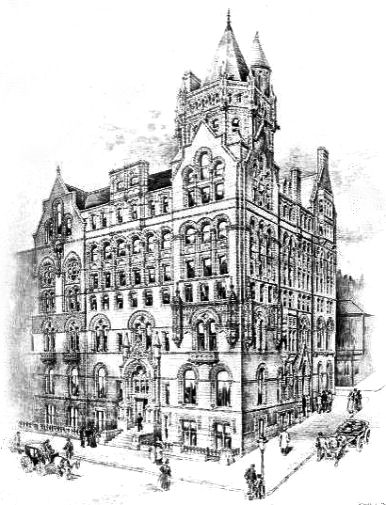

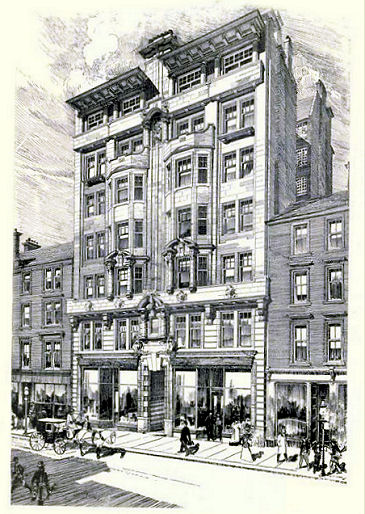

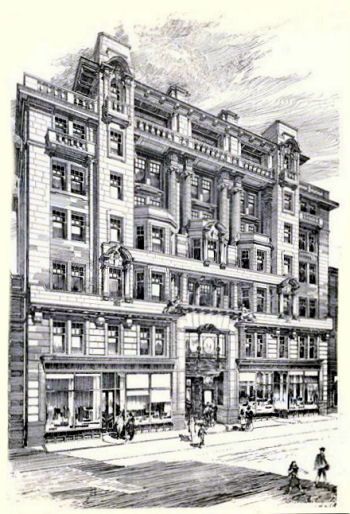

Having successfully sidestepped any responsibility for the unfortunate deaths of the employees of Templeton's Carpet Factory, Leiper continued in his career as one of the famous "Glasgow Architects”. He moved on to try his hand at designing a monumental city centre office block in the Scottish version of the grandiose Beaux-Arts style which featured numerous sculptured embellishments on their highly decorative frontages. William Leiper's Sun Life Building at the corner of Renfield Street and West George Street was completed at the end of 1894. It is regarded as his most conspicuous contribution to the commercial architecture of Glasgow's city centre. The drawing (below left) was displayed at the annual exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, in 1893. The photograph (below, right) of the completed block was exhibited over a decade later at the annual exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy of 1904.

Exhibition images of Sun Life Building, Glasgow, designed by William Leiper

Sun Life Building, Glasgow, August 2016

Sun Life Building was adorned by the works of celebrated sculptor, William Birnie Rhind. The decorative panel below was displayed at the annual exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh, in 1894. The lavish use of external sculpture was a feature of Glasgow's Beaux-Arts styled buildings.

Sculpted panel at Sun Life Building by William Birnie Rhind

The most "over the top" example of this style of building was the highly elaborate Bible Training Institute at the corner of Bothwell Street and West Campbell Street. The pre-existing Christian Institute was extended in 1896 by the architectural partnership of Clarke & Bell whose exhibition drawing is shown below.

Exhibition images of Bible Training Institute & YMCA, Glasgow, Clarke & Bell, Architects

At the annual exhibition of the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts in 1899, drawings were displayed of three different sets of chambers in Glasgow city centre. These monumental sandstone fronted office blocks contained lots of little rooms separated by brick partitions.

With the exception of the corner suites, each set of windows in the massive façade represents one of the small individual offices shown in the plan. There are further small offices gaining natural light from windows facing the central "Open Court".

Baltic Chambers, Glasgow, 1899

Example of compartmentalised office space viewed from below

The drawings below show the other chambers, displayed at the same exhibition as Baltic Chambers in 1899.

Atlantic Chambers (left) and Waterloo Chambers (right), Glasgow, 1899

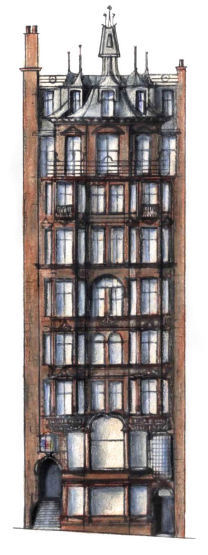

In St Vincent Street, at the heart of Glasgow's business district, you will find James Salmon's slender 1902 office block, the Hatrack. Hatrack Building

The Hatrack's integral framework allowed the architect to create large areas of glass surrounded by a minimal amount of decorative stone, giving the façade a lightness and modernity for which Salmon and some of the more adventurous Glasgow architects were gaining a worldwide reputation at the time. The masonry on the Hatrack's façade is merely a facing, being part of a 3 dimensional "curtain wall" which doesn't carry any dead loads from the building as would be expected in traditional sandstone construction. The effect of depth is enhanced by the use of bay windows, recessed arched windows and projecting iron and stone balconies. The building's exterior was tastefully decorated in the Glasgow style, using the same modern construction methods which gave Gaudi the freedom to realise his fantasies in Barcelona around the same time.

Salmon's drawing of the Hatrack Building, below, was displayed at the annual exhibition of the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts in 1900.

James Salmon's drawing of the Hatrack Building, 1900

I suspect that Salmon was inspired by Oriel Chambers in Liverpool, built in 1864, which features a skeletal frame encased in fine sandstone allowing the use of large areas of glass in its elevations to the streets.

Like Glasgow, Liverpool was a trans-Atlantic port and both cities were open to modernistic ideas which were also shaping the cities of the United States. The sheer originality of Oriel Chambers aroused much local controversy in Liverpool.

Its innovative architect, Peter Ellis, was thought to be extremely daring in a city which took great pride in its wonderful Victorian neo-classical architecture.

Orient House

The ubiquitous concrete and steel structures of the present era go back as far as the 19th century in Glasgow. The overall theme of the composition is Italian Renaissance, but the use of novel materials gives the building a feel quite unlike other warehouses of the period. Tomb of William James Anderson at Cathcart Cemetery

Anderson's experimental construction methods were developed further by one of his former pupils at Glasgow School of Art, James Salmon, in the design of Lion Chambers on the east side of Hope Street.

In April 1995 the 7 co-owners of the block were refused planning permission for its demolition owing to the historical and architectural novelty of the structure which made it a category "A" listed building. Protective metal mesh was placed around the external shell to hold together the disintegrating concrete. Photograph of Lion Chambers displayed at the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts Exhibition, 1907

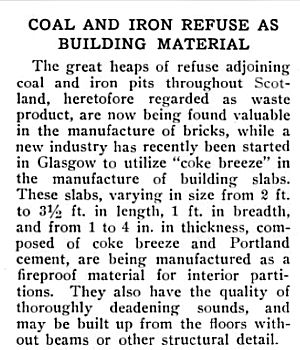

Glasgow was in the forefront of mass-produced factory-made concrete building materials. Earlier forms of structural concrete had been made "in situ" as far back as the 1870's with Alexander Thomson's Egyptian Halls.

This news article from 1911 describes a new industry starting in Glasgow, manufacturing concrete slabs and breeze blocks which were described as "bricks" at the time. The prefabricated slabs came in various sizes with widths varying from one to four inches. The materials used to create these new products were very abundant and were previously thought to have no value. The "breeze" or "clinker" was found in the residue left after the burning process to produce gas and coke.

Before the introduction of breeze blocks, heavier concrete blocks with aggregates of gravel or broken stone were used. The new breeze blocks and clinker concrete slabs helped make robust lightweight structures, but it was hard to convince traditionalists that the new lighter products were as structurally sound as the heavier versions.

Street scene showing Hunter Barr Building, Queen Street, 1907

Not all Glasgow's architects and their clients embraced modern construction ideas. The formation of multi-storey office blocks by traditional methods, however, becomes impracticable once you reach a certain height. The example, left, shows the seven-storey Hunter Barr Building in Queen Street, designed by David Barclay, which was built between 1899 and 1903.

The grey lead sheeting at three different levels indicates where the wall thickness changes, getting progressively heavier as you go down towards the street.

It was built on the "Wedding Cake" principle, where the lower storeys had to be very substantial indeed in order to carry the load of the upper levels, which you can see are not exactly lightweight!

When this building was converted into modern open-plan offices, as the "Guild Hall" in 1986, it was Scotland's first major atrium office scheme.

The view, right, is from the rear of the building after the redevelopment. Atrium and elevator at Guild Hall, Glasgow

By the 1920's and 1930's steel-framed buildings were becoming more

commonplace in Glasgow. Local architects were finding the confidence to imitate the monumental structures of North American cities which the general public were now able to see in the movies. In the United States, the 19th century cast-iron buildings had rapidly evolved into steel framed skyskrapers. Structural steel, which has a lesser carbon content than cast iron, contains other metallic elements to give it the tensile strength which is required for multi-storey construction.

One of the finest examples of American inspired architecture in Glasgow is the Scottish

Legal Life Assurance Society block in Bothwell Street, which was completed in 1931.

It was designed by Edward Grigg Wylie of the locally based partnership of Wright & Wylie.

Night view of Scottish Legal Life Assurance Society Building, Bothwell Street

James Miller, Architect

James Miller, who was a master of many architectural techniques, used American styling for the Glasgow chief office of the Bank of Scotland, which was originally built for the Union Bank. The completion year of 1927 is inscribed in the stonework to assist we students of architectural history. The impressive edifice can be viewed from either St Vincent or Renfield Street, where it dominates the corner. Union Bank of Scotland, St Vincent Street

Structural steelwork for Union Bank of Scotland, 1925

In July 2005, as part of an £18.4 million redevelopment scheme, permission was granted to tear down the original floors of the Union Bank, retaining only the façades and the banking hall from the original building.

The photograph, right, was taken from St Vincent Street and features the south façade illuminated by the midday sun. It was shot in December 2005, during the demolition work on the upper storeys.

New structure appearing from rooftop, September 2006

Aerial view of city block showing modern offices behind original bank façade

Photograph of newly completed Union Bank of Scotland, 1927

'James Miller House', at corner of West George Street and West Nile Street

Now known as 'James Miller House', this block was built as the Glasgow Branch of the Commercial Bank of Scotland. The six-storey building, which is situated at the corner of West George Street and West Nile Street, was designed by James Miller in 1930. It was faced with white Portland stone with a contrasting black marble plinth. Like the nearby Union Bank it had an extra tall ground floor banking hall with marble finishes.

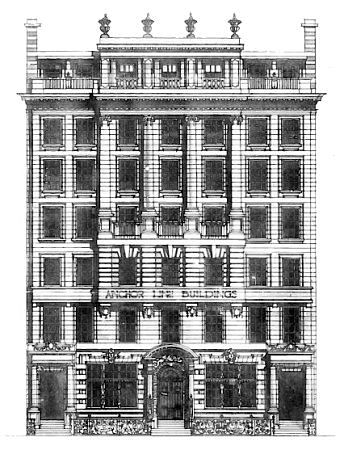

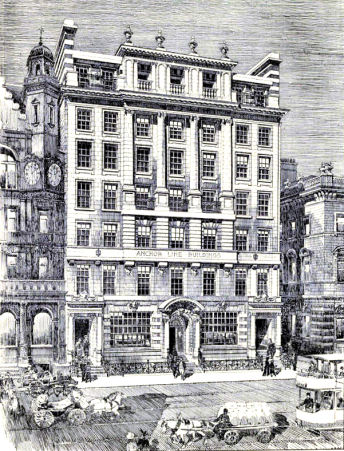

An earlier example of James Miller's American influenced designs can be found in the Anchor Line Building in St. Vincent Place, designed and built in 1906-1907 and situated a few blocks away from the Union Bank.

Anchor Line Building, St. Vincent Place, Glasgow

The Anchor Line Building was designed with seven bays and seven storeys. It was fitted with a fururistic "Express Passenger Electric Lift" to gain rapid access to the uppermost levels.

Elevation and perspective drawing of Anchor Line Building, Glasgow, by James Miller

Miller's perspective drawing of the Anchor Line Building (above right) was displayed at the architectural exhibition of the Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts in 1908.

The 'Anchor Line' Licensed Restaurant opened for business in September 2014.

The interior retains many of the original features which were originally designed to mimic the luxurious finishes of an ocean liner, with Miller having also designed the interiors of the SS Lusitania.

Signature of James Miller A.R.S.A from architect's blueprint

If you wish to see further examples of how early 20th century commercial Glasgow architecture compared with that in the United States, my American Landmark Buildings webpage includes drawings of cast iron fronted and steel framed buildings in New York City.

White Anchor Line Building shown alongide clock of red sandstone Evening Citizen Building in St. Vincent Place

Exhibition drawing of Evening Citizen Offices from 1893, before erection of Anchor Line Building

On the opposite side of St Vincent Place you can find the monumental Scottish Provident Building, designed in the French Renaissance style by John M D Peddie.

Scottish Provident Building, St Vincent Place, c.1908

1930's street scene showing 'old and new' commercial buildings in Glasgow city centre

Large-scale production of industrial ironware had began in the area as far back as

1786, the year when the Clyde Ironworks were established in Tollcross.

The Carswell brothers,

William (died 1852) and James (died 1856), were responsible over a 65-year period for

many of the utilitarian premises resulting from this expansion.

The obituary to James Carswell in the Glasgow Herald of 25th February 1856 states

that "they were in their day the most extensive contractors as wrights in the city". It

goes on to say that

"the Carswells were the first to introduce iron pillars in buildings, as well as iron

fronts and facings ".

The obituary informs us that the brothers came to Glasgow from Kilmarnock in 1790 and erected their workshops on a clearing they had created from a cornfield, adjacent

to a footpath which would later become George Street.

This type of building was an intermediate step towards the fully framed multi-storey structures which were soon to follow. The external masonry was loadbearing; the floors were carried on timber joists or wrought iron beams, supported internally on cast iron columns and externally on the masonry walls.

The green netting in this example is required to protect the disintegrating stuccowork, rather than the ironwork.

The façades to both Jamaica Street and Midland Street are fashioned entirely in cast iron and plate glass following a simple and graceful pattern. Its designer, John Baird, used the innovative materials to produce a structure of extraordinary elegance and lightness.

Gardners had been in the forefront of the Glasgow furniture trade for over 150 years from 1832 to 1985, when the company was acquired by their Edinburgh rivals Martin and Frost.

In August 2000, after an extensive refurbishment, the building re-opened as a bar/restaurant with the new title of the Crystal Palace. It is now one of the largest and brightest pubs in Glasgow city centre. It has lots of natural light from the seemingly endless glazing to keep the window cleaner (right) very busy!

Workmen pushing hand carts and passengers on a horse drawn omnibus are seen alongside top-hatted gentlemen on horseback and ladies going about their business.

Otis had demonstrated his elevator in spectacular fashion at the New York Fair of 1854, when he cut the hoisting cable to show the lift being held fast by an automatic safety mechanism. His invention paved the way for the development of practical multi-storey buildings which evolved into skyscrapers with the coming of structural steel.

Sadly nothing now remains of this historically important part of Glasgow's architectural heritage.

Had the building survived it would possibly have been the earliest example of this kind of construction to be found anywhere.

The glass-fronted warehouse, which was completed in 1872, was designed by John Honeyman

with a high roofed shopping arcade at ground level.

In keeping with the times, the patrons of the luncheon room on the 2nd floor were entertained with live music

from the resident orchestra. The gentlemen could then enjoy the facilities of the smoking rooms on the floor above. The two storey

banqueting hall, an ugly addition to the roof from around 1925, was converted into a popular ballroom in the 1950's. The reconstructed version of the Ca' D'Oro now has a slated

roof, which is much more in keeping with the rest of the structure.

150 years ago, the providers of warehouse space on both sides of the Atlantic anticipated modern practice where architects can select prefabricated components to meet the needs of commercial projects.

Macfarlane's ironwork was shipped to places as far away as India, Brazil, South Africa, Australia and the West Indies.

His earliest city centre warehouses had more in common with his domestic and ecclesiastical commissions, but in 1868 he boldly experimented with iron elements in the frontage for the Buck's Head building in Argyle Street.

The paintwork on the exotically styled external iron pillars (left) was beautifully restored as part of a total make-over which was completed in 2003.

In 1998 the upper floors were stripped back to their original form in preparation for future construction work which never materialised.

In May 2008 plans were finalised to bring the whole building into the single ownership of Union Street Properties, who intended to carry out a major refurbishment scheme.

In September 2010, it was announced that funding problems had delayed the start of any work on the building. Historic Scotland offered the developers just £1.5m for external stone repairs and nothing at all towards the restoration of the cast iron structure.

Various other funding sources are also now threatened.

The visit gave me fascinating insight into the construction methods of the 1870's.

The original design, which we unfortunately cannot now admire, was by architect John Gordon in 1878. The upper storeys were described at the time of construction as being "handsomely ornamented, balustraded and arcaded in a richly carved design".

The original building was designed by local architects Clarke & Bell and opened for use in 1873. The new complex opened in July 2010.

It was built for Robert Humphries between 1816 and 1821 in a very plain functional style, with no attempt to provide a grand façade which would have been demanded by entrepreneurs later in the century.

The building was converted for use as offices in 1998.

The fresher coloured brickwork at the lift shaft for the elevators serving the upper two storeys could be an indication that that the block had been extended upwards at a later date from the original construction.

The above retained façade in Ingram Street was one of three similar developments in progress in the same area during early 2003.

It was a bit like the Victorian ladies' fashions, where you were never meant to know anything about the metal caged crinolines under the stylish dresses!

The elaborate façade provided perfect cover for the conventional iron-framed Victorian mill hiding behind it, designed by engineers, Messrs J.B. Harvey.

This type of block is easy to date as "turn of the century" as it was faced with red sandstone rather than the more familiar cream sandstone from the local Giffnock quarries, which had become exhausted by that time.

The original building designed by architect John McLeod opened in 1879. Rising maintenace costs resulted in the demolition of the building in the summer of 1980.

The architect of Baltic Chambers was Duncan McNaughtan and his perspective drawing and upper floor plan are shown below.

This compartmentalised type of block was not readily adaptable for the modern requirements for open-plan office space, hence the adopted solution of façade retention and total reconstruction behind it.

This narrow eight storey structure has an extraordinary rooftop, quite unlike any other in the city, which led to the building's title. It was thought more to resemble a piece of ornate furniture than a functional roof.

Liverpool also has what is considered to be Britain's first ever skyscraper, the Royal Liver Building, which was built in 1911. The steel and concrete structure was designed by W. A. Thomas to have 13 floor levels, making it much higher than any comparable building of the time.

My drawings of both Oriel Chambers and the Liver Building are featured in my English Architecture – Iconic Buildings

web page.

Orient House in Cowcaddens, which was completed in 1895, is the best preserved Victorian example of the style. It was designed by William J Anderson, who was appointed as Dean of Architecture at Glasgow School of Art in 1894, during the building's construction. This was the time when the innovative ideas of Glasgow architects such as the young Charles Rennie Mackintosh were in their formative stages.

Anderson died in 1900, unaware of how popular his experimental methods of construction would turn out to be in the new century.

It was constructed with a steel frame and internal steel beams, with concrete floors and ceilings.

The external walls have a stucco finish which further emphasise the Italianate style. It had a flat concrete roof finished with asphalt, which would have been very unusual in Glasgow's rainy climate.

In between periods of commercial use, the Orient building was used as a lodging house.

It became unoccupied in the early 1970's and, after a long period of abandonment, was converted into flats.

It has been suggested that a fatal accident in 1899 in one of Anderson's unconventional structures was a contributory factor in his early death at his own hands at the age of 36.

Salmon and his partner, John. G. Gillespie, produced a modernistic building which was perhaps too ambitious for 1907 when it was completed. It was built with lightweight reinforced concrete with a conventional outward appearance which disguises the fact that the external walls are only 4 inches thick. From the 4th storey upwards the tower stands on its own without the support of the adjoining block. On these upper levels there are very small common landings leading to a narrow staircase, less than 6 feet wide, tagged on to the side of the building.

The structure was fabricated with the patented "Hennebique Ferro-Concrete" system, which was widely used for civil engineering projects at the time.

Lion Chambers is currently unoccupied after the last unit was vacated in late 2009 by G A H Douglas & Co, who had been one of the original occupants in 1907. It will remain an empty shell until the money and the collective will is found for refurbishment.

A more likely scenario, given the probable cost of renovation, is that the owners will be granted their wish to pull it down.

The strength of the blocks was determined by the proportions of water, cement and clinker in the mix. Concrete products manufactured in the early twentieth century lacked the conformity of more modern ones and varied in strength, but many of them have survived to the present day.

Lead flashings are commonly seen on roofs to provide protection from rainfall but the differences in wall depths in this building are so substantial that protection is required for the progressively thicker stonework at each layer.

Behind the massive façade, four distinct steel-framed structures were erected around a central atrium, which has a glazed roof providing natural light to the core of the block. Within this interior courtyard, glass fronted elevators glide up the full height of the building. The atrium concept is intended to provide ample means of escape and containment of fire, should it break out on any particular section.

The scale of the building has to be witnessed first hand. The Ionic columns at the front stretch up over the first 3 storeys, which includes the banking hall which has more office space above it.

The rebuilt structure, completed in the summer of 2007, has six levels of modern office space and a new glazed rooftop storey.

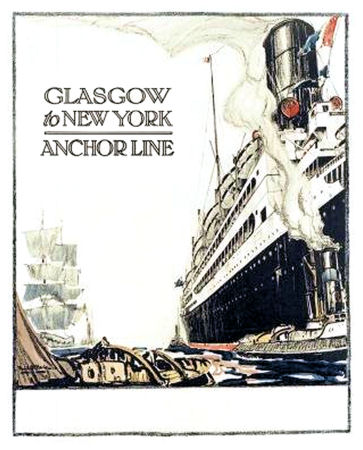

The Anchor Line operated trans-Atlantic liners, sailing from Glasgow and Liverpool to New York City and the rest of the world.

The block was faced with brilliant white "Carrara ware", an imitation marble conceived by Henry Doulton in 1888 which was described as being "impervious to water and damp, and not affected by atmospheric influences, either as regards decay or losing its colour".

This boast has proved to have been accurate over a century later, with the building retaining its original polished white finish without blemish.

![]()

|

| |

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All original artwork, photography and text © Gerald Blaikie

Unauthorised reproduction of any image on this website is not permitted.